What Sub Types Are Considered Arts and Craft Style Homes

The Arts and crafts motility was an international trend in the decorative and fine arts that developed earliest and most fully in the British Isles[one] and later spread across the British Empire and to the residual of Europe and America.[2]

Initiated in reaction against the perceived impoverishment of the decorative arts and the conditions in which they were produced,[three] the movement flourished in Europe and North America between well-nigh 1880 and 1920. It is the root of the Modernistic Style, the British expression of what later came to be chosen the Art Nouveau movement, which it strongly influenced.[4] In Japan it emerged in the 1920s as the Mingei movement. It stood for traditional craftsmanship, and often used medieval, romantic, or folk styles of decoration. Information technology advocated economic and social reform and was anti-industrial in its orientation.[3] [5] It had a strong influence on the arts in Europe until information technology was displaced past Modernism in the 1930s,[one] and its influence continued amid craft makers, designers, and town planners long later.[6]

The term was beginning used by T. J. Cobden-Sanderson at a meeting of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society in 1887,[7] although the principles and style on which it was based had been developing in England for at least 20 years. It was inspired by the ideas of architect Augustus Pugin, writer John Ruskin, and designer William Morris.[8] In Scotland it is associated with fundamental figures such every bit Charles Rennie Mackintosh.[ix]

Origins and influences [edit]

Design reform [edit]

The Arts and Crafts movement emerged from the attempt to reform design and decoration in mid-19th century United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland. Information technology was a reaction against a perceived decline in standards that the reformers associated with machinery and manufacturing plant production. Their critique was sharpened by the items that they saw in the Keen Exhibition of 1851, which they considered to be excessively ornate, artificial, and ignorant of the qualities of the materials used. Fine art historian Nikolaus Pevsner writes that the exhibits showed "ignorance of that basic need in creating patterns, the integrity of the surface", as well as displaying "vulgarity in detail".[x] Pattern reform began with Exhibition organizers Henry Cole (1808–1882), Owen Jones (1809–1874), Matthew Digby Wyatt (1820–1877), and Richard Redgrave (1804–1888),[xi] all of whom deprecated excessive decoration and impractical or badly made things.[12] The organizers were "unanimous in their condemnation of the exhibits."[13] Owen Jones, for instance, complained that "the builder, the upholsterer, the newspaper-stainer, the weaver, the calico-printer, and the potter" produced "novelty without beauty, or beauty without intelligence."[xiii] From these criticisms of manufactured goods emerged several publications which gear up out what the writers considered to exist the right principles of design. Richard Redgrave's Supplementary Written report on Design (1852) analysed the principles of design and ornament and pleaded for "more logic in the application of ornament."[12] Other works followed in a similar vein, such equally Wyatt'due south Industrial Arts of the Nineteenth Century (1853), Gottfried Semper's Wissenschaft, Industrie und Kunst ("Science, Industry and Art") (1852), Ralph Wornum's Analysis of Ornament (1856), Redgrave's Transmission of Design (1876), and Jones's Grammar of Decoration (1856).[12] The Grammar of Ornament was peculiarly influential, liberally distributed as a pupil prize and running into nine reprints past 1910.[12]

Jones declared that ornament "must be secondary to the thing decorated", that at that place must exist "fitness in the decoration to the thing ornamented", and that wallpapers and carpets must not have any patterns "suggestive of anything but a level or obviously".[fourteen] A textile or wallpaper in the Great Exhibition might be decorated with a natural motif made to look as existent as possible, whereas these writers advocated apartment and simplified natural motifs. Redgrave insisted that "way" demanded sound structure before decoration, and a proper sensation of the quality of materials used. "Utility must have precedence over ornamentation."[15]

The Nature of Gothic past John Ruskin, printed by William Morris at the Kelmscott Printing in 1892 in his Golden Type inspired by 15th century printer Nicolas Jenson. This chapter from The Stones of Venice (book) was a sort of manifesto for the Arts and Crafts move.

However, the design reformers of the mid-19th century did not become as far every bit the designers of the Arts and crafts move. They were more concerned with ornamentation than construction, they had an incomplete understanding of methods of manufacture,[15] and they did non criticise industrial methods as such. By contrast, the Craft movement was every bit much a movement of social reform equally blueprint reform, and its leading practitioners did not separate the two.

A. Due west. N. Pugin [edit]

Pugin'due south house "The Grange" in Ramsgate, 1843. Its simplified Gothic style, adapted to domestic edifice, helped shape the architecture of the Arts and Crafts move.

Some of the ideas of the movement were anticipated by A. W. N. Pugin (1812–1852), a leader in the Gothic revival in architecture. For example, he advocated truth to textile, structure, and function, as did the Craft artists.[16] Pugin articulated the tendency of social critics to compare the faults of mod lodge with the Eye Ages,[17] such as the sprawling growth of cities and the treatment of the poor – a tendency that became routine with Ruskin, Morris, and the Craft motion. His volume Contrasts (1836) drew examples of bad mod buildings and town planning in contrast with skillful medieval examples, and his biographer Rosemary Loma notes that he "reached conclusions, almost in passing, nearly the importance of craftsmanship and tradition in architecture that it would accept the balance of the century and the combined efforts of Ruskin and Morris to work out in detail." She describes the spare furnishings which he specified for a building in 1841, "rush chairs, oak tables", as "the Arts and Crafts interior in embryo."[17]

John Ruskin [edit]

The Craft philosophy was derived in big measure from John Ruskin's social criticism, deeply influenced by the work of Thomas Carlyle.[18] Ruskin related the moral and social wellness of a nation to the qualities of its architecture and to the nature of its work. Ruskin considered the sort of mechanized production and partitioning of labour that had been created in the industrial revolution to be "servile labour", and he thought that a good for you and moral social club required independent workers who designed the things that they fabricated. He believed factory-made works to exist "dishonest," and that handwork and craftsmanship merged dignity with labour.[19] His followers favoured arts and crafts production over industrial manufacture and were concerned nearly the loss of traditional skills, but they were more troubled past the effects of the mill system than by machinery itself.[20] William Morris'south idea of "handicraft" was essentially work without any division of labour rather than work without any sort of mechanism.[21]

William Morris [edit]

William Morris, a textile designer who was a key influence on the Craft move

William Morris (1834–1896) was the towering figure in late 19th-century design and the chief influence on the Arts and Crafts movement. The artful and social vision of the movement grew out of ideas that he adult in the 1850s with the Birmingham Set – a group of students at the Academy of Oxford including Edward Burne-Jones, who combined a love of Romantic literature with a commitment to social reform.[22] John William Mackail notes that "Carlyle's Past and Present stood alongside of [Ruskin's] Modern Painters as inspired and accented truth."[23] The medievalism of Mallory'due south Morte d'Arthur set the standard for their early style.[24] In Burne-Jones' words, they intended to "wage Holy warfare against the historic period".[25]

William Morris'southward Red House in Bexleyheath, designed past Philip Webb and completed in 1860; one of the most significant buildings of the Arts and Crafts movement[26]

Morris began experimenting with diverse crafts and designing piece of furniture and interiors.[27] He was personally involved in manufacture too every bit design,[27] which was the authentication of the Arts and Crafts motion. Ruskin had argued that the separation of the intellectual human action of pattern from the manual act of physical cosmos was both socially and aesthetically damaging. Morris further developed this thought, insisting that no work should be carried out in his workshops before he had personally mastered the appropriate techniques and materials, arguing that "without dignified, creative human occupation people became disconnected from life".[27]

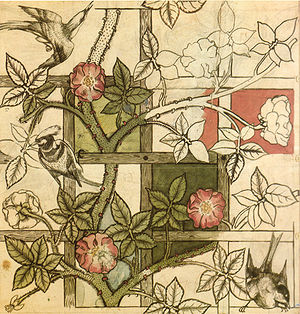

The weaving shed in Morris & Co's factory at Merton, which opened in the 1880s

In 1861, Morris began making furniture and decorative objects commercially, modelling his designs on medieval styles and using bold forms and strong colours. His patterns were based on flora and fauna, and his products were inspired by the colloquial or domestic traditions of the British countryside. Some were deliberately left unfinished in order to display the beauty of the materials and the work of the craftsman, thus creating a rustic appearance. Morris strove to unite all the arts inside the ornament of the home, emphasizing nature and simplicity of form.[28]

Social and design principles [edit]

Unlike their counterparts in the United States, most Arts and Crafts practitioners in Britain had stiff, slightly incoherent, negative feelings nigh mechanism. They idea of 'the craftsman' equally free, creative, and working with his easily, 'the machine' every bit soulless, repetitive, and inhuman. These contrasting images derive in office from John Ruskin'south (1819–1900) The Stones of Venice, an architectural history of Venice that contains a powerful denunciation of modern industrialism to which Arts and crafts designers returned again and again. Distrust for the machine lay backside the many little workshops that turned their backs on the industrial globe around 1900, using preindustrial techniques to create what they called 'crafts.'

— Alan Crawford, "W. A. Southward. Benson, Machinery, and the Craft Movement in Britain"[29]

Critique of manufacture [edit]

William Morris shared Ruskin'south critique of industrial society and at one time or another attacked the mod factory, the use of machinery, the sectionalisation of labour, capitalism and the loss of traditional craft methods. But his attitude to machinery was inconsistent. He said at one betoken that production past machinery was "altogether an evil",[10] but at others times, he was willing to commission work from manufacturers who were able to see his standards with the assist of machines.[30] Morris said that in a "true society", where neither luxuries nor inexpensive trash were made, mechanism could be improved and used to reduce the hours of labour.[31] Fiona MacCarthy says that "unlike subsequently zealots like Gandhi, William Morris had no practical objections to the utilize of machinery per se so long as the machines produced the quality he needed."[32]

Morris insisted that the creative person should exist a craftsman-designer working past hand[10] and advocated a lodge of free craftspeople, such as he believed had existed during the Eye Ages. "Because craftsmen took pleasure in their work", he wrote, "the Middle Ages was a period of greatness in the art of the common people. ... The treasures in our museums now are but the mutual utensils used in households of that age, when hundreds of medieval churches – each i a masterpiece – were built by unsophisticated peasants."[33] Medieval fine art was the model for much of Arts and Crafts design, and medieval life, literature and edifice was idealised by the movement.

Morris's followers also had differing views almost machinery and the factory organization. For instance, C. R. Ashbee, a central figure in the Arts and Crafts motion, said in 1888, that, "Nosotros do not reject the auto, we welcome information technology. Simply we would desire to encounter information technology mastered."[10] [34] After unsuccessfully pitting his Gild and School of Handicraft social club confronting modernistic methods of manufacture, he acknowledged that "Modern culture rests on machinery",[10] just he continued to criticise the deleterious effects of what he chosen "mechanism", proverb that "the production of certain mechanical bolt is as bad for the national health as is the production of slave-grown cane or kid-sweated wares."[35] William Arthur Smith Benson, on the other hand, had no qualms about adapting the Arts and Crafts style to metalwork produced under industrial conditions. (See quotation box.)

Morris and his followers believed the division of labour on which modern manufacture depended was undesirable, merely the extent to which every design should be carried out by the designer was a matter for debate and disagreement. Not all Arts and Crafts artists carried out every phase in the making of goods themselves, and it was but in the twentieth century that that became essential to the definition of craftsmanship. Although Morris was famous for getting hands-on experience himself of many crafts (including weaving, dying, printing, calligraphy and embroidery), he did non regard the separation of designer and executant in his manufacturing plant as problematic. Walter Crane, a close political associate of Morris's, took an unsympathetic view of the sectionalization of labour on both moral and artistic grounds, and strongly advocated that designing and making should come from the same paw. Lewis Foreman Day, a friend and contemporary of Crane's, as unstinting equally Crane in his adoration of Morris, disagreed strongly with Crane. He idea that the separation of design and execution was not only inevitable in the modernistic world, but too that only that sort of specialisation allowed the best in blueprint and the best in making.[36] Few of the founders of the Craft Exhibition Lodge insisted that the designer should besides be the maker. Peter Floud, writing in the 1950s, said that "The founders of the Society ... never executed their ain designs, merely invariably turned them over to commercial firms."[37] The idea that the designer should be the maker and the maker the designer derived "non from Morris or early on Arts and crafts teaching, only rather from the second-generation elaboration doctrine worked out in the commencement decade of [the twentieth] century by men such as Due west. R. Lethaby".[37]

[edit]

Many of the Arts and Crafts movement designers were socialists, including Morris, T. J. Cobden Sanderson, Walter Crane, C.R. Ashbee, Philip Webb, Charles Faulkner, and A. H. Mackmurdo.[38] In the early 1880s, Morris was spending more of his fourth dimension on promoting socialism than on designing and making.[39] Ashbee established a community of craftsmen called the Guild of Handicraft in eastward London, subsequently moving to Chipping Campden.[vii] Those adherents who were non socialists, such equally Alfred Hoare Powell,[20] advocated a more humane and personal relationship betwixt employer and employee. Lewis Foreman Twenty-four hours was some other successful and influential Arts and crafts designer who was not a socialist, despite his long friendship with Crane.

Association with other reform movements [edit]

In Britain, the movement was associated with dress reform,[40] ruralism, the garden urban center movement[6] and the folk-song revival. All were linked, in some caste, past the ideal of "the Unproblematic Life".[41] In continental Europe the movement was associated with the preservation of national traditions in building, the applied arts, domestic design and costume.[42]

Evolution [edit]

Morris's designs quickly became popular, attracting interest when his company's work was exhibited at the 1862 International Exhibition in London. Much of Morris & Co'due south early on piece of work was for churches and Morris won important interior design commissions at St James's Palace and the S Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum). Later his piece of work became popular with the middle and upper classes, despite his wish to create a democratic art, and by the end of the 19th century, Arts and Crafts design in houses and domestic interiors was the ascendant style in Britain, copied in products made by conventional industrial methods.

The spread of Arts and crafts ideas during the belatedly 19th and early 20th centuries resulted in the institution of many associations and craft communities, although Morris had little to do with them because of his preoccupation with socialism at the time. A hundred and thirty Arts and Crafts organisations were formed in Uk, nigh betwixt 1895 and 1905.[43]

In 1881, Eglantyne Louisa Jebb, Mary Fraser Tytler and others initiated the Home Arts and Industries Clan to encourage the working classes, especially those in rural areas, to take upwards handicrafts under supervision, not for profit, but in gild to provide them with useful occupations and to ameliorate their gustatory modality. By 1889 it had 450 classes, i,000 teachers and 5,000 students.[44]

In 1882, architect A.H.Mackmurdo formed the Century Order, a partnership of designers including Selwyn Paradigm, Herbert Horne, Cloudless Heaton and Benjamin Creswick.[45] [46]

In 1884, the Fine art Workers Social club was initiated by v young architects, William Lethaby, Edward Prior, Ernest Newton, Mervyn Macartney and Gerald C. Horsley, with the goal of bringing together fine and practical arts and raising the condition of the latter. Information technology was directed originally by George Blackall Simonds. Past 1890 the Lodge had 150 members, representing the increasing number of practitioners of the Arts and Crafts style.[47] Information technology nonetheless exists.

The London department store Liberty & Co., founded in 1875, was a prominent retailer of goods in the mode and of the "creative apparel" favoured by followers of the Arts and crafts movement.

In 1887 the Craft Exhibition Society, which gave its proper noun to the movement, was formed with Walter Crane as president, holding its first exhibition in the New Gallery, London, in November 1888.[48] It was the beginning bear witness of contemporary decorative arts in London since the Grosvenor Gallery's Winter Exhibition of 1881.[49] Morris & Co. was well represented in the exhibition with furniture, fabrics, carpets and embroideries. Edward Burne-Jones observed, "here for the first time ane can measure a bit the alter that has happened in the last 20 years".[50] The society still exists as the Society of Designer Craftsmen.[51]

In 1888, C.R.Ashbee, a major belatedly practitioner of the style in England, founded the Guild and School of Handicraft in the East Finish of London. The club was a arts and crafts branch modelled on the medieval guilds and intended to give working men satisfaction in their adroitness. Skilled craftsmen, working on the principles of Ruskin and Morris, were to produce manus-crafted goods and manage a school for apprentices. The thought was greeted with enthusiasm past well-nigh anybody except Morris, who was past now involved with promoting socialism and idea Ashbee's scheme trivial. From 1888 to 1902 the guild prospered, employing about 50 men. In 1902 Ashbee relocated the guild out of London to brainstorm an experimental customs in Chipping Campden in the Cotswolds. The guild's work is characterised by plain surfaces of hammered silvery, flowing wirework and colored stones in uncomplicated settings. Ashbee designed jewellery and silvery tableware. The guild flourished at Chipping Camden but did non prosper and was liquidated in 1908. Some craftsmen stayed, contributing to the tradition of modern craftsmanship in the area.[sixteen] [52] [53]

C.F.A. Voysey (1857–1941) was an Arts and crafts architect who also designed fabrics, tiles, ceramics, furniture and metalwork. His way combined simplicity with sophistication. His wallpapers and textiles, featuring stylised bird and plant forms in bold outlines with flat colors, were used widely.[xvi]

Morris'southward thought influenced the distributism of 1000. Grand. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc.[54]

Coleton Fishacre was designed in 1925 as a vacation dwelling in Kingswear, Devon, England, in the Arts and Crafts tradition.

Past the end of the nineteenth century, Arts and crafts ethics had influenced architecture, painting, sculpture, graphics, illustration, volume making and photography, domestic pattern and the decorative arts, including piece of furniture and woodwork, stained glass,[55] leatherwork, lacemaking, embroidery, carpet making and weaving, jewelry and metalwork, enameling and ceramics.[56] By 1910, there was a fashion for "Arts and Crafts" and all things hand-fabricated. There was a proliferation of amateur handicrafts of variable quality[57] and of incompetent imitators who acquired the public to regard Arts and Crafts as "something less, instead of more than, competent and fit for purpose than an ordinary mass produced commodity."[58]

The Arts and Crafts Exhibition Order held eleven exhibitions between 1888 and 1916. By the outbreak of war in 1914 it was in decline and faced a crisis. Its 1912 exhibition had been a fiscal failure.[59] While designers in continental Europe were making innovations in design and alliances with manufacture through initiatives such equally the Deutsche Werkbund and new initiatives were beingness taken in Britain by the Omega Workshops and the Design in Industries Association, the Arts and crafts Exhibition Guild, now under the control of an old baby-sit, was withdrawing from commerce and collaboration with manufacturers into purist handwork and what Tania Harrod describes every bit "decommoditisation"[59] Its rejection of a commercial part has been seen equally a turning point in its fortunes.[59] Nikolaus Pevsner in his book Pioneers of Modernistic Blueprint presents the Arts and crafts motion as design radicals who influenced the modern movement, merely failed to alter and were eventually superseded by information technology.[ten]

Later influences [edit]

The British artist potter Bernard Leach brought to England many ideas he had adult in Nihon with the social critic Yanagi Soetsu well-nigh the moral and social value of simple crafts; both were enthusiastic readers of Ruskin. Leach was an active propagandist for these ideas, which struck a chord with practitioners of the crafts in the inter-war years, and he expounded them in A Potter's Volume, published in 1940, which denounced industrial society in terms equally trigger-happy as those of Ruskin and Morris. Thus the Arts and Crafts philosophy was perpetuated among British craft workers in the 1950s and 1960s, long after the demise of the Arts and Crafts move and at the high tide of Modernism. British Utility article of furniture of the 1940s also derived from Arts and crafts principles.[threescore] One of its primary promoters, Gordon Russell, chairman of the Utility Furniture Design Console, was imbued with Arts and crafts ideas. He manufactured article of furniture in the Cotswold Hills, a region of Arts and Crafts article of furniture-making since Ashbee, and he was a member of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Lodge. William Morris'southward biographer, Fiona MacCarthy, detected the Arts and crafts philosophy even backside the Festival of Britain (1951), the work of the designer Terence Conran (b. 1931)[6] and the founding of the British Crafts Council in the 1970s.[61]

By region [edit]

The British Isles [edit]

Stained glass window, The Colina House, Helensburgh, Argyll and Bute

Scotland [edit]

The beginnings of the Arts and Crafts motility in Scotland were in the stained glass revival of the 1850s, pioneered by James Ballantine (1808–1877). His major works included the groovy west window of Dunfermline Abbey and the scheme for St. Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh. In Glasgow it was pioneered by Daniel Cottier (1838–1891), who had probably studied with Ballantine, and was directly influenced by William Morris, Ford Madox Brown and John Ruskin. His key works included the Baptism of Christ in Paisley Abbey, (c. 1880). His followers included Stephen Adam and his son of the same name.[62] The Glasgow-born designer and theorist Christopher Dresser (1834–1904) was one of the first, and most important, contained designers, a pivotal figure in the Aesthetic Movement and a major correspondent to the allied Anglo-Japanese movement.[63] The motion had an "boggling flowering" in Scotland where it was represented by the development of the 'Glasgow Fashion' which was based on the talent of the Glasgow School of Art. Celtic revival took agree hither, and motifs such equally the Glasgow rose became popularised. Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928) and the Glasgow Schoolhouse of Fine art were to influence others worldwide.[1] [56]

Wales [edit]

The situation in Wales was different than elsewhere in the UK. Insofar as adroitness was concerned, Craft was a revivalist campaign. But in Wales, at least until World War I, a genuine craft tradition yet existed. Local materials, stone or dirt, continued to be used as a matter of course.[64]

Scotland become known in the Arts and crafts movement for its stained glass; Wales would become known for its pottery. By the mid 19th century, the heavy, salt glazes used for generations by local craftsmen had gone out of style, non least as mass-produced ceramics undercut prices. Merely the Arts and Crafts Movement brought new appreciation to their work. Horace W Elliot, an English gallerist, visited the Ewenny Pottery (which dated back to the 17th century) in 1885, to both find local pieces and encourage a mode compatible with the movement.[65] The pieces he brought back to London for the next xx years revivified interest in Welsh pottery work.

A key promoter of the Arts and Crafts move in Wales was Owen Morgan Edwards. Edwards was a reforming politician dedicated to renewing Welsh pride by exposing its people to their ain language and history. For Edwards, "There is nothing that Wales requires more than than an education in the craft."[66] – though Edwards was more inclined to resurrecting Welsh Nationalism than admiring glazes or rustic integrity.[67]

In architecture, Clough Williams-Ellis sought to renew involvement in ancient edifice, reviving "rammed earth" or pisé[ane] structure in U.k..

Republic of ireland [edit]

The movement spread to Ireland, representing an important fourth dimension for the nation'south cultural evolution, a visual analogue to the literary revival of the same time[68] and was a publication of Irish nationalism. The Craft employ of stained glass was popular in Ireland, with Harry Clarke the all-time-known artist and too with Evie Hone. The compages of the manner is represented by the Honan Chapel (1916) in Cork metropolis in the grounds of University College Cork.[69] Other architects practicing in Ireland included Sir Edwin Lutyens (Heywood House in Co. Laois, Lambay Island and the Irish gaelic National State of war Memorial Gardens in Dublin) and Frederick 'Pa' Hicks (Malahide Castle estate buildings and round tower). Irish Celtic motifs were popular with the move in silvercraft, rug design, book illustrations and hand-carved article of furniture.

Continental Europe [edit]

In continental Europe, the revival and preservation of national styles was an important motive of Arts and Crafts designers; for instance, in Germany, later unification in 1871 nether the encouragement of the Bund für Heimatschutz (1897)[70] and the Vereinigte Werkstätten für Kunst im Handwerk founded in 1898 by Karl Schmidt; and in Hungary Károly Kós revived the vernacular style of Transylvanian edifice. In primal Europe, where several diverse nationalities lived under powerful empires (Germany, Republic of austria-Hungary and Russia), the discovery of the vernacular was associated with the exclamation of national pride and the striving for independence, and, whereas for Arts and Crafts practitioners in Uk the ideal fashion was to be plant in the medieval, in central Europe it was sought in remote peasant villages.[71]

Widely exhibited in Europe, the Arts and Crafts fashion'due south simplicity inspired designers like Henry van de Velde and styles such as Fine art Nouveau, the Dutch De Stijl grouping, Vienna Secession, and eventually the Bauhaus mode. Pevsner regarded the style as a prelude to Modernism, which used simple forms without ornamentation.[10]

The earliest Arts and Crafts action in continental Europe was in Belgium in nearly 1890, where the English style inspired artists and architects including Henry Van de Velde, Gabriel Van Dievoet, Gustave Serrurier-Bovy and a group known as La Libre Esthétique (Complimentary Aesthetic).

Arts and crafts products were admired in Republic of austria and Federal republic of germany in the early on 20th century, and under their inspiration blueprint moved rapidly forrard while information technology stagnated in United kingdom.[72] The Wiener Werkstätte, founded in 1903 by Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser, was influenced by the Arts and crafts principles of the "unity of the arts" and the hand-made. The Deutscher Werkbund (High german Association of Craftsmen) was formed in 1907 every bit an association of artists, architects, designers, and industrialists to ameliorate the global competitiveness of German businesses and became an important element in the development of modern architecture and industrial design through its advocacy of standardized production. However, its leading members, van de Velde and Hermann Muthesius, had alien opinions about standardization. Muthesius believed that information technology was essential were Frg to become a leading nation in trade and civilisation. Van de Velde, representing a more traditional Arts and crafts attitude, believed that artists would forever "protest against the imposition of orders or standardization," and that "The creative person ... will never, of his ain accord, submit to a discipline which imposes on him a catechism or a blazon." [73]

In Republic of finland, an idealistic artists' colony in Helsinki was designed by Herman Gesellius, Armas Lindgren and Eliel Saarinen,[ane] who worked in the National Romantic style, alike to the British Gothic Revival.

In Hungary, under the influence of Ruskin and Morris, a group of artists and architects, including Károly Kós, Aladár Körösfői-Kriesch and Ede Toroczkai Wigand, discovered the folk art and colloquial architecture of Transylvania. Many of Kós'south buildings, including those in the Budapest zoo and the Wekerle estate in the same city, evidence this influence.[74]

In Russia, Viktor Hartmann, Viktor Vasnetsov, Yelena Polenova and other artists associated with Abramtsevo Colony sought to revive the quality of medieval Russian decorative arts quite independently from the movement in Neat Great britain.

In Republic of iceland, Sölvi Helgason's piece of work shows Arts and crafts influence.

Northward America [edit]

Warren Wilson Embankment Business firm (The Venice Beach Firm), Venice, California

Gamble House, Pasadena, California

Arts and Crafts Tudor Domicile in the Buena Park Historic District, Uptown, Chicago

Example of Arts and crafts way influence on Federation architecture Observe the faceted bay window and the rock base.

Arts and Crafts abode in the Birckhead Place neighborhood of Toledo, Ohio

In the United States, the Craft style initiated a variety of attempts to reinterpret European Arts and Crafts ideals for Americans. These included the "Craftsman"-manner architecture, furniture, and other decorative arts such every bit designs promoted by Gustav Stickley in his magazine, The Craftsman and designs produced on the Roycroft campus as publicized in Elbert Hubbard'due south The Fra. Both men used their magazines every bit a vehicle to promote the appurtenances produced with the Craftsman workshop in Eastwood, NY and Elbert Hubbard's Roycroft campus in Due east Aurora, NY. A host of imitators of Stickley'southward piece of furniture (the designs of which are often mislabelled the "Mission Fashion") included three companies established by his brothers.

The terms American Craftsman or Craftsman style are oft used to denote the manner of architecture, interior blueprint, and decorative arts that prevailed between the dominant eras of Fine art Nouveau and Art Deco in the United states, or approximately the menstruum from 1910 to 1925. The move was particularly notable for the professional person opportunities it opened up for women as artisans, designers and entrepreneurs who founded and ran, or were employed by, such successful enterprises as the Kalo Shops, Pewabic Pottery, Rookwood Pottery, and Tiffany Studios. In Canada, the term Arts and crafts predominates, but Craftsman is also recognized.[75]

While the Europeans tried to recreate the virtuous crafts beingness replaced past industrialisation, Americans tried to found a new type of virtue to replace heroic craft product: well-decorated middle-course homes. They claimed that the simple but refined aesthetics of Arts and Crafts decorative arts would ennoble the new experience of industrial consumerism, making individuals more than rational and lodge more harmonious. The American Arts and crafts movement was the aesthetic counterpart of its gimmicky political philosophy, progressivism. Characteristically, when the Arts and Crafts Society began in October 1897 in Chicago, information technology was at Hull House, one of the first American settlement houses for social reform.[76]

Arts and Crafts ethics disseminated in America through journal and newspaper writing were supplemented by societies that sponsored lectures.[76] The outset was organized in Boston in the late 1890s, when a group of influential architects, designers, and educators adamant to bring to America the blueprint reforms begun in Britain by William Morris; they met to organize an exhibition of contemporary arts and crafts objects. The first coming together was held on Jan iv, 1897, at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) in Boston to organize an exhibition of contemporary crafts. When craftsmen, consumers, and manufacturers realised the aesthetic and technical potential of the applied arts, the procedure of design reform in Boston started. Present at this meeting were General Charles Loring, Chairman of the Trustees of the MFA; William Sturgis Bigelow and Denman Ross, collectors, writers and MFA trustees; Ross Turner, painter; Sylvester Baxter, art critic for the Boston Transcript; Howard Baker, A.W. Longfellow Jr.; and Ralph Clipson Sturgis, builder.

The first American Arts and crafts Exhibition began on April five, 1897, at Copley Hall, Boston featuring more than 1000 objects fabricated by 160 craftsmen, half of whom were women.[77] Some of the advocates of the exhibit were Langford Warren, founder of Harvard'due south School of Compages; Mrs. Richard Morris Hunt; Arthur Astor Carey and Edwin Mead, social reformers; and Will H. Bradley, graphic designer. The success of this exhibition resulted in the incorporation of The Social club of Arts and crafts (SAC), on June 28, 1897, with a mandate to "develop and encourage college standards in the handicrafts." The 21 founders claimed to be interested in more than sales, and emphasized encouragement of artists to produce work with the best quality of workmanship and design. This mandate was soon expanded into a credo, possibly written by the SAC'south starting time president, Charles Eliot Norton, which read:

This Order was incorporated for the purpose of promoting artistic work in all branches of handicraft. It hopes to bring Designers and Workmen into mutually helpful relations, and to encourage workmen to execute designs of their own. Information technology endeavors to stimulate in workmen an appreciation of the dignity and value of good design; to annul the popular impatience of Constabulary and Form, and the desire for over-ornamentation and specious originality. Information technology will insist upon the necessity of sobriety and restraint, or ordered arrangement, of due regard for the relation between the form of an object and its utilize, and of harmony and fitness in the ornament put upon it.[78]

Built in 1913–14 by the Boston builder J. Williams Beal in the Ossipee Mountains of New Hampshire, Tom and Olive Establish'due south mountaintop estate, Castle in the Clouds likewise known every bit Lucknow, is an excellent example of the American Craftsman manner in New England.[79]

Likewise influential were the Roycroft customs initiated by Elbert Hubbard in Buffalo and East Aurora, New York, Joseph Marbella, utopian communities like Byrdcliffe Colony in Woodstock, New York, and Rose Valley, Pennsylvania, developments such as Mountain Lakes, New Jersey, featuring clusters of bungalow and chateau homes built by Herbert J. Hapgood, and the contemporary studio craft fashion. Studio pottery – exemplified by the Grueby Faience Visitor, Newcomb Pottery in New Orleans, Marblehead Pottery, Teco pottery, Overbeck and Rookwood pottery and Mary Hunt Perry Stratton's Pewabic Pottery in Detroit, the Van Briggle Pottery company in Colorado Springs, Colorado, equally well as the fine art tiles made past Ernest A. Batchelder in Pasadena, California, and idiosyncratic furniture of Charles Rohlfs all demonstrate the influence of Arts and crafts.

Architecture and Art [edit]

The "Prairie School" of Frank Lloyd Wright, George Washington Maher and other architects in Chicago, the Land Solar day School movement, the bungalow and ultimate bungalow fashion of houses popularized by Greene and Greene, Julia Morgan, and Bernard Maybeck are some examples of the American Arts and Crafts and American Craftsman style of architecture. Restored and landmark-protected examples are still present in America, peculiarly in California in Berkeley and Pasadena, and the sections of other towns originally developed during the era and not experiencing post-war urban renewal. Mission Revival, Prairie School, and the 'California bungalow' styles of residential building remain popular in the The states today.

As theoreticians, educators, and prolific artists in mediums from printmaking to pottery and pastel, two of the near influential figures were Arthur Wesley Dow (1857–1922) on the East Coast and Pedro Joseph de Lemos (1882–1954) in California. Dow, who taught at Columbia University and founded the Ipswich Summer School of Art, published in 1899 his landmark Composition, which distilled into a distinctly American approach the essence of Japanese composition, combining into a decorative harmonious constructing three elements: simplicity of line, "notan" (the balance of light and dark areas), and symmetry of color.[80] His purpose was to create objects that were finely crafted and beautifully rendered. His student de Lemos, who became head of the San Francisco Art Institute, Director of the Stanford University Museum and Fine art Gallery, and Editor-in-Chief of the School Arts Magazine, expanded and substantially revised Dow's ideas in over 150 monographs and articles for art schools in the United states and Britain.[81] Among his many unorthodox teachings was his belief that manufactured products could express "the sublime beauty" and that great insight was to exist found in the abstruse "design forms" of pre-Columbian civilizations.

Museums [edit]

The Museum of the American Arts and Crafts Move in St. Petersburg, Florida, opened its doors in 2019.[82] [83]

Asia [edit]

In Japan, Yanagi Sōetsu, creator of the Mingei movement which promoted folk art from the 1920s onwards, was influenced by the writings of Morris and Ruskin.[33] Like the Craft movement in Europe, Mingei sought to preserve traditional crafts in the face of modernising industry.

Compages [edit]

The motion ... represents in some sense a defection against the hard mechanical conventional life and its insensibility to beauty (quite some other matter to ornament). Information technology is a protest against that then-called industrial progress which produces shoddy wares, the cheapness of which is paid for past the lives of their producers and the degradation of their users. It is a protest confronting the turning of men into machines, confronting artificial distinctions in art, and against making the immediate market value, or possibility of turn a profit, the principal test of artistic merit. It besides advances the merits of all and each to the common possession of dazzler in things common and familiar, and would awaken the sense of this beauty, deadened and depressed every bit it now too often is, either on the ane manus past luxurious superfluities, or on the other past the absence of the commonest necessities and the gnawing anxiety for the means of livelihood; non to speak of the everyday uglinesses to which we take accustomed our eyes, dislocated by the flood of false gustation, or darkened by the hurried life of mod towns in which huge aggregations of humanity exist, as removed from both art and nature and their kindly and refining influences.

-- Walter Crane, "Of The Revival of Pattern and Handicraft", in Arts and Crafts Essays, by Members of the Craft Exhibition Society, 1893

Many of the leaders of the Arts and Crafts move were trained as architects (eastward.g. William Morris, A. H. Mackmurdo, C. R. Ashbee, W. R. Lethaby) and it was on building that the motion had its near visible and lasting influence.

Red House, in Bexleyheath, London, designed for Morris in 1859 by architect Philip Webb, exemplifies the early on Arts and crafts way, with its well-proportioned solid forms, broad porches, steep roof, pointed window arches, brick fireplaces and wooden fittings. Webb rejected classical and other revivals of historical styles based on grand buildings, and based his design on British colloquial compages, expressing the texture of ordinary materials, such as stone and tiles, with an asymmetrical and picturesque building limerick.[16]

The London suburb of Bedford Park, built mainly in the 1880s and 1890s, has about 360 Arts and Crafts fashion houses and was once famous for its Aesthetic residents. Several Almshouses were built in the Arts and Crafts style, for example, Whiteley Village, Surrey, built between 1914 and 1917, with over 280 buildings, and the Dyers Almshouses, Sussex, congenital betwixt 1939 and 1971. Letchworth Garden City, the offset garden urban center, was inspired by Arts and Crafts ethics.[6] The kickoff houses were designed by Barry Parker and Raymond Unwin in the vernacular style popularized by the move and the boondocks became associated with high-mindedness and simple living. The sandal-making workshop set up by Edward Carpenter moved from Yorkshire to Letchworth Garden City and George Orwell's jibe about "every fruit-juice drinker, nudist, sandal-wearer, sexual practice-maniac, Quaker, 'Nature Cure' dishonest, pacifist, and feminist in England" going to a socialist conference in Letchworth has become famous.[84]

Architectural examples [edit]

- Red House – Bexleyheath, Kent – 1859

- David Parr House – Cambridge, England – 1886–1926

- Wightwick Estate – Wolverhampton, England – 1887–93

- Inglewood – Leicester, England – 1892

- Standen – Eastward Grinstead, England – 1894

- Swedenborgian Church – San Francisco, California – 1895

- Mary Ward House – Bloomsbury, London – 1896–98

- Blackwell – Lake Commune, England – 1898

- Derwent House – Chislehurst, Kent – 1899

- Stoneywell – Ulverscroft, Leicestershire – 1899

- The Arts & Crafts Church (Long Street Methodist Church and School) – Manchester, England – 1900

- Spade House – Sandgate, Kent – 1900

- Caledonian Estate – Islington, London – 1900–1907

- Horniman Museum – Forest Loma, London – 1901

- All Saints' Church, Brockhampton – 1901–02

- Shaw'due south Corner – Ayot St Lawrence, Hertfordshire – 1902

- Pierre P. Ferry House – Seattle, Washington – 1903–1906

- Winterbourne Firm – Birmingham, England – 1904

- The Black Friar – Blackfriars, London – 1905

- Marston Business firm – San Diego, California – 1905

- Edgar Wood Center – Manchester, England – 1905

- Debenham Firm – Holland Park, London – 1905–07

- Robert R. Blacker Business firm – Pasadena, California – 1907

- Stotfold, Bickley, Kent – 1907

- Risk House – Pasadena, California – 1908

- Oregon Public Library – Oregon, Illinois – 1909

- Thorsen House – Berkeley, California – 1909

- Rodmarton Manor – Rodmarton, near Cirencester, Gloucestershire – 1909–29

- Whare Ra – Havelock Due north, New Zealand – 1912

- Sutton Garden Suburb – Benhilton, Sutton, London – 1912–14

- Castle in the Clouds – Ossipee Mountains at Lake Winnipesaukee, New Hampshire – 1913-4

- Honan Chapel – Academy Higher Cork, Ireland – c.1916

- St Francis Xavier'south Cathedral – Geraldton Western Australia 1916–1938

- Bedales School Memorial Library – near Petersfield, Hampshire – 1919–21

Garden design [edit]

Gertrude Jekyll applied Arts and Crafts principles to garden design. She worked with the English architect, Sir Edwin Lutyens, for whose projects she created numerous landscapes, and who designed her abode Munstead Wood, nearly Godalming in Surrey.[85] Jekyll created the gardens for Bishopsbarns,[86] the home of York architect Walter Brierley, an exponent of the Craft movement and known as the "Lutyens of the North".[87] The garden for Brierley's final project, Goddards in York, was the piece of work of George Dillistone, a gardener who worked with Lutyens and Jekyll at Castle Drogo.[88] At Goddards the garden incorporated a number of features that reflected the craft style of the business firm, such as the use of hedges and herbaceous borders to dissever the garden into a series of outdoor rooms.[89] Another notable Craft garden is Hidcote Manor Garden designed by Lawrence Johnston which is also laid out in a series of outdoor rooms and where, like Goddards, the landscaping becomes less formal further away from the house.[90] Other examples of Arts and Crafts gardens include Hestercombe Gardens, Lytes Cary Manor and the gardens of some of the architectural examples of craft buildings (listed higher up).

Art teaching [edit]

Morris's ideas were adopted past the New Education Movement in the late 1880s, which incorporated handicraft teaching in schools at Abbotsholme (1889) and Bedales (1892), and his influence has been noted in the social experiments of Dartington Hall during the mid-20th century.[61]

Craft practitioners in Great britain were critical of the government organization of art pedagogy based on pattern in the abstract with little teaching of practical craft. This lack of craft preparation also caused business organisation in industrial and official circles, and in 1884 a Royal Commission (accepting the communication of William Morris) recommended that fine art education should pay more attending to the suitability of blueprint to the cloth in which information technology was to be executed.[91] The first schoolhouse to make this modify was the Birmingham School of Arts and crafts, which "led the way in introducing executed design to the teaching of art and design nationally (working in the material for which the design was intended rather than designing on paper). In his external examiner's report of 1889, Walter Crane praised Birmingham School of Fine art in that information technology 'considered blueprint in relationship to materials and usage.'"[92] Nether the direction of Edward Taylor, its headmaster from 1877 to 1903, and with the help of Henry Payne and Joseph Southall, the Birmingham School became a leading Arts-and-Crafts eye.[93]

George Frampton. Season ticket to The Arts and Craft Exhibition Society 1890.

Other local authorization schools besides began to introduce more than applied educational activity of crafts, and by the 1890s Craft ideals were being disseminated past members of the Art Workers Guild into art schools throughout the country. Members of the Gild held influential positions: Walter Crane was director of the Manchester Schoolhouse of Art and subsequently the Royal College of Art; F.M. Simpson, Robert Anning Bell and C.J.Allen were respectively professor of architecture, instructor in painting and design, and teacher in sculpture at Liverpool School of Art; Robert Catterson-Smith, the headmaster of the Birmingham Art School from 1902 to 1920, was besides an AWG member; W. R. Lethaby and George Frampton were inspectors and advisors to the London County Council's (LCC) education lath and in 1896, largely as a result of their work, the LCC gear up up the Central Schoolhouse of Arts and Crafts and made them joint principals.[94] Until the germination of the Bauhaus in Germany, the Central Schoolhouse was regarded as the most progressive fine art school in Europe.[95] Shortly after its foundation, the Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts was fix on Craft lines by the local borough council.

As head of the Regal College of Fine art in 1898, Crane tried to reform it forth more practical lines, only resigned after a year, defeated by the bureaucracy of the Board of Educational activity, who then appointed Augustus Spencer to implement his program. Spencer brought in Lethaby to head its school of design and several members of the Fine art Workers' Guild every bit teachers.[94] Ten years later on reform, a committee of inquiry reviewed the RCA and institute that it was nonetheless non fairly training students for industry.[96] In the debate that followed the publication of the committee's report, C.R.Ashbee published a highly critical essay, Should We Stop Instruction Art, in which he chosen for the system of art instruction to be completely dismantled and for the crafts to be learned in land-subsidised workshops instead.[97] Lewis Foreman 24-hour interval, an important figure in the Arts and Crafts movement, took a dissimilar view in his dissenting report to the committee of inquiry, arguing for greater emphasis on principles of design against the growing orthodoxy of teaching pattern by direct working in materials. Nevertheless, the Arts and Crafts ethos thoroughly pervaded British fine art schools and persisted, in the view of the historian of art pedagogy, Stuart MacDonald, until after the Second World War.[94]

Leading practitioners [edit]

- Charles Robert Ashbee

- William Swinden Hairdresser

- Barnsley brothers

- Detmar Blow

- Herbert Tudor Buckland

- Rowland Wilfred William Carter

- T. J. Cobden-Sanderson

- Walter Crane

- Nelson Dawson

- Lewis Foreman Day

- Christopher Dresser

- Dirk van Erp

- Thomas Phillips Figgis

- Eric Gill

- Ernest Gimson

- Greene & Greene

- Elbert Hubbard

- Norman Jewson

- Ralph Johonnot

- Florence Koehler

- Frederick Leach

- William Lethaby

- Edwin Lutyens

- Charles Rennie Mackintosh

- A.H.Mackmurdo

- Samuel Maclure

- George Washington Maher

- Bernard Maybeck

- Henry Chapman Mercer

- Julia Morgan

- William De Morgan

- William Morris

- Karl Parsons

- Alfred Hoare Powell

- Edward Schroeder Prior

- Hugh C. Robertson

- William Robinson

- Baillie Scott

- Norman Shaw

- Ellen Gates Starr

- Gustav Stickley

- Phoebe Anna Traquair

- C.F.A. Voysey

- Philip Webb

- Margaret Ely Webb

- Christopher Whall

- Edgar Wood

- Charles Rohlfs

Decorative arts gallery [edit]

See also [edit]

- Modern Way (British Art Nouveau mode)

- Philip Clissett

- The English House

- Charles Prendergast

- William Morris wallpaper designs

- William Morris textile designs

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d Campbell, Gordon (2006). The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts, Book ane. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-19-518948-3.

- ^ Wendy Kaplan and Alan Crawford, The Arts & Crafts movement in Europe & America: Design for the Mod World, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- ^ a b Brenda M. King, Silk and Empire

- ^ "Craft movement | British and international movement". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Moses North. Ikiugu and Elizabeth A. Ciaravino, Psychosocial Conceptual Exercise models in Occupational Therapy; "Arts and Crafts Style Guide". British Galleries. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 17 July 2007.

- ^ a b c d Fiona MacCarthy, Chaos and Dazzler: William Morris and his Legacy 1860–1960, London: National Portrait Gallery, 2014 ISBN 978 185514 484 2

- ^ a b Alan Crawford, C. R. Ashbee: Builder, Designer & Romantic Socialist, Yale University Press, 2005. ISBN 0300109393

- ^ Triggs, Oscar Lovell (1902). Chapters in the History of the Arts and crafts Movement. Bohemia Guild of the Industrial Art League.

- ^ Sumpner, Dave; Morrison, Julia (28 February 2020). My Revision Notes: Pearson Edexcel A Level Design and Technology (Production Design). Hodder Education. ISBN978-one-5104-7422-two.

- ^ a b c d e f 1000 Nikolaus Pevsner, Pioneers of Modern Pattern, Yale University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-300-10571-1

- ^ "V&A, "Wallpaper Design Reform"".

- ^ a b c d Naylor 1971, p. 21.

- ^ a b Naylor 1971, p. 20.

- ^ Quoted in Nikolaus Pevsner, Pioneers of Modern Blueprint

- ^ a b Naylor 1971, p. 22.

- ^ a b c d "Victoria and Albert Museum". Vam.ac.great britain. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ a b Rosemary Hill, God's Builder: Pugin and the Building of Romantic Britain, London: Allen Lane, 2007

- ^ Blakesley, Rosalind P. (2009). The Craft Movement. Phaidon Press. ISBN 978-0714849676.

- ^ "John Ruskin – Artist Philosopher Writer – Arts & Crafts Leader". www.arts-crafts.com. Archived from the original on xviii December 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ a b Jacqueline Sarsby" Alfred Powell: Idealism and Realism in the Cotswolds", Periodical of Design History, Vol. 10, No. four, pp. 375–397

- ^ David Pye, The Nature and Fine art of Workmanship, Cambridge University Press, 1968

- ^ Naylor 1971, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Mackail, J. W. (2011). The Life of William Morris. New York: Dover Publications. p. 38. ISBN 978-0486287935.

- ^ Wildman 1998, p. 49.

- ^ Naylor 1971, p. 97.

- ^ "National Trust, "Iconic Arts and Crafts home of William Morris"".

- ^ a b c MacCarthy 2009.

- ^ "The Arts and Crafts Movement in America". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2019. Retrieved xvi March 2019.

- ^ Alan Crawford, "W. A. S. Benson, Machinery, and the Arts and Crafts Movement in Britain", The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts, Vol. 24, Design, Civilisation, Identity: The Wolfsonian Drove (2002), pp. 94–117

- ^ Graeme Shankland, "William Morris – Designer", in Asa Briggs (ed.) William Morris: Selected Writings and Designs, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1980 ISBN 0-fourteen-020521-7

- ^ William Morris, "Useful Work versus Useless Toil", in Asa Briggs (ed.) William Morris: Selected Writings and Designs, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1980 ISBN 0-14-020521-seven

- ^ MacCarthy 1994, p. 351.

- ^ a b Elisabeth Frolet, Nick Pearce, Soetsu Yanagi and Sori Yanagi, Mingei: The Living Tradition in Japanese Arts, Japan Folk Crafts Museum/Glasgow Museums, Japan: Kodashani International, 1991

- ^ Ashbee, C. R., A Few Chapters on Workshop Construction and Citizenship, London, 1894.

- ^ "C. R. Ashbee, Should We Cease Pedagogy Art?, New York and London: Garland, 1978, p.12 (Facsimile of the 1911 edition)

- ^ "Designer and Executant: An Argument Between Walter Crane and Lewis Foreman Day".

- ^ a b Peter Floud, "The crafts and so and at present", The Studio, 1953, p.127

- ^ Naylor 1971, p. 109.

- ^ MacCarthy 1994, p. 640-663.

- ^ "V&A, "Victorian Dress at the V&A"".

- ^ Fiona McCarthy. The Simple Life, Lund Humphries, 1981

- ^ "Arts and crafts movement". Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ MacCarthy 1994, p. 602.

- ^ Naylor 1971, p. 120.

- ^ MacCarthy 1994, p. 591.

- ^ Naylor 1971, p. 115.

- ^ MacCarthy 1994, p. 593.

- ^ Parry, Linda, William Morris and the Arts and Crafts Movement: A Sourcebook, New York, Portland House, 1989 ISBN 0-517-69260-0

- ^ "Crane, Walter, "Of the Arts and Crafts Motility", in Ethics In Art: Papers Theoretical Practical Critical, George Bell & Sons, 1905". Chestofbooks.com. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ MacCarthy 1994, p. 596.

- ^ "Society of Designer Craftsmen". Club of Designer Craftsmen. Retrieved 28 Baronial 2010.

- ^ "Utopia Britannica". Utopia Britannica. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ "Court Barn Museum". Courtbarn.org.united kingdom. Archived from the original on 29 Jan 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ Letter, Joseph Nuttgens, London Review of Books, 13 May 2010 p iv

- ^ Cormack, Peter (2015). Craft Stained Drinking glass (First ed.). New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN978-0-300-20970-9.

- ^ a b Nicola Gordon Bowe and Elizabeth Cumming, The Craft Movements in Dublin and Edinburgh

- ^ "Arts and crafts", Periodical of the Royal Social club of Arts, Vol. 56, No. 2918, 23 Oct 1908, pp. 1023–1024

- ^ Noel Rooke, "The Craftsman and Education for Industry", in Four Papers Read past Members of the Arts & Crafts Exhibition Lodge, London: Craft Exhibition Order, 1935

- ^ a b c Tania Harrod, The Crafts in U.k. in the 20th Century, Yale University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-300-07780-7

- ^ Designing Britain Archived May fifteen, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b MacCarthy 1994, p. 603.

- ^ Thou. MacDonald, Scottish Fine art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000), ISBN 0500203334, p. 151.

- ^ H. Lyons, Christopher Dresser: The People Designer – 1834–1904 (Antiquarian Collectors' Club, 2005), ISBN 1851494553.

- ^ Hilling, John B. (15 August 2018). The Architecture of Wales: From the First to the 20-First Century. University of Wales Press. p. 221. ISBN978-1-78683-285-6. 'Craft' to Early on Modernism, 1900 to 1939

- ^ Aslet, Clive (4 Oct 2010). Villages of Britain: The Five Hundred Villages that Made the Countryside. A&C Black. p. 477. ISBN978-0-7475-8872-6.

- ^ Davies, Hazel; Council, Welsh Arts (one Jan 1988). O. One thousand. Edwards. University of Wales Press on behalf of Welsh Arts Council. p. 28. ISBN9780708309971. Sec. 3

- ^ Rothkirch, Alyce von; Williams, Daniel (2004). Beyond the Difference: Welsh Literature in Comparative Contexts : Essays for G. Wynn Thomas at Sixty. Academy of Wales Printing. p. 10. ISBN978-0-7083-1886-7.

- ^ Nicola Gordon Bowe, The Irish Craft Movement (1886–1925), Irish Arts Review Yearbook, 1990–91, pp. 172–185

- ^ Teehan & Heckett 2005, p. 163.

- ^ Ákos Moravánszky, Competing visions: aesthetic invention and social imagination in Cardinal European Compages 1867–1918, Massachusetts Plant of Technology, 1998

- ^ Andrej Szczerski, "Central Europe", in Karen Livingstone and Linda Parry (eds.), International Arts and crafts, London: V&A Publications, 2005

- ^ Naylor 1971, p. 183.

- ^ Naylor 1971, p. 189.

- ^ Széleky András, Kós Károly, Budapest, 1979

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Fine art: Monica Obniski, "The Arts and crafts Movement in America"". Metmuseum.org. 20 February 1972. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ^ a b Obniski.

- ^ "The Arts & Crafts Movement – Concepts & Styles". The Art Story . Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ Brandt, Beverly Kay. The Craftsman and the Critic: Defining Usefulness and Beauty in the Craft-era Boston. University of Massachusetts Press, 2009. p. 113.

- ^ Cahn, Lauren. (March 13, 2019) "The Most Famous House in Every State. Image #29: Castle in the Clouds" MSN.com website. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ Green, Nancy Due east. and Jessie Poesch (1999). Arthur Wesley Dow and American arts & crafts. New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. pp. 55–126. ISBN0810942178.

- ^ Edwards, Robert W. (2015). Pedro de Lemos, Lasting Impressions: Works on Paper. Worcester, Mass.: Davis Publications Inc. pp. 4–111. ISBN9781615284054.

- ^ "Structure Begins on $40 Million Museum of the American Arts & Crafts in Florida". ARTFIX Daily. 18 February 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ^ Nichols, Steve (18 February 2015). "New, bigger, art museum coming to St. Pete". Play tricks 13 Pinellas Agency Reporter. Archived from the original on 21 Feb 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ^ George Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier

- ^ Tankard, Judith B. and Martin A. Woods. Gertrude Jekyll at Munstead Wood. Bramley Books, 1998.

- ^ Historic England. "Bishopsbarns (1256793)". National Heritage List for England . Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ "The Art of Design" (PDF). world wide web.nationaltrust.org.great britain . Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ^ Historic England. "Castle Drogo park and garden (1000452)". National Heritage List for England . Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ^ "The Gardens at Goddards". world wide web.nationaltrust.org.uk . Retrieved 26 June 2016.

- ^ "The Garden at Hidcote". www.nationaltrust.org.uk . Retrieved six July 2016.

- ^ Charles Harvey and Jon Printing, "William Morris and the Royal Commission on Technical Didactics", Journal of the William Morris Gild 11.1, August 1994, pp. 31–34 Archived 2015-01-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ ""Birmingham Plant of Art and Design" fineart.ac.uk".

- ^ Everitt, Sian. "Keeper of Archives". Birmingham Establish of Art and Design . Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ^ a b c Stuart Macdonald, The History and Philosophy of Art Educational activity, London: University of London Press, 1970. ISBN 0 340 09420 6

- ^ Naylor 1971, p. 179.

- ^ Written report of the Departmental Commission on the Royal Higher of Fine art, HMSO, 1911

- ^ C.R.Ashbee, Should We Stop Teaching Art?, 1911

Bibliography and further reading [edit]

- Ayers, Dianne (2002). American Arts and Crafts Textiles. New York: Harry Due north. Abrams. ISBN0-8109-0434-9.

- Blakesley, Rosalind P. The arts and crafts motility (Phaidon, 2006).

- Boris, Eileen (1986). Art and Labor . Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN0-87722-384-X.

- Carruthers, Annette. The Craft Move in Scotland: A History (2013) online review

- Cathers, David M. (1981). Furniture of the American Arts and crafts Motility. The New American Library, Inc. ISBN0-453-00397-4.

- Cathers, David Chiliad. (2014). So Various Are The Forms Information technology Assumes: American Arts & Crafts Article of furniture from the Two Red Roses Foundation. Marquand Books. ISBN978-0-692-21348-3.

- Cathers, David M. (20 Feb 2017). These Humbler Metals: Arts and Crafts Metalwork from the Two Cherry Roses Foundation Drove. Marquand Books. ISBN978-0-615-98869-6.

- Cormack, Peter. Arts & crafts stained glass (Yale Up, 2015).

- Cumming, Elizabeth; Kaplan, Wendy (1991). Arts & Crafts Movement. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN0-500-20248-6.

- Cumming, Elizabeth (2006). Hand, Eye and Soul: The Arts and crafts Movement in Scotland. Birlinn. ISBN978-ane-84158-419-5.

- Danahay, Martin. "Arts and Crafts equally a Transatlantic Movement: CR Ashbee in the Us, 1896–1915." Periodical of Victorian Culture twenty.one (2015): 65–86.

- Greensted, Mary. The arts and crafts motility in Great britain (Shire, 2010).

- Johnson, Bruce (2012). Arts & Crafts Shopmarks. Fletcher, NC: Knock On Wood Publications. ISBN978-one-4507-9024-6.

- Kaplan, Wendy (1987). The Art that Is Life: The Arts & Crafts Movement in America 1875-1920. New York: Little, Dark-brown and Company.

- Kreisman, Lawrence, and Glenn Mason. The Arts & Craft Motion in the Pacific Northwest (Timber Press, 2007).

- Krugh, Michele. "Joy in labour: The politicization of arts and crafts from the arts and crafts movement to Etsy." Canadian Review of American Studies 44.2 (2014): 281–301. online

- Luckman, Susan. "Precarious labour then and now: The British arts and crafts movement and cultural piece of work revisited." Theorizing Cultural Work (Routledge, 2014) pp. 33–43 online.

- MacCarthy, Fiona (2009). "Morris, William (1834–1896), designer, writer, and visionary socialist". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19322. (Subscription or Great britain public library membership required.)

- MacCarthy, Fiona (1994). William Morris. Faber and Faber. ISBN0-571-17495-7.

- Mascia-Lees, Frances Due east. "American Beauty: The Middle Class Arts and Crafts Revival in the U.s.." in Critical Craft (Routledge, 2020) pp. 57–77.

- Meister, Maureen. Craft Compages: History and Heritage in New England (UP of New England, 2014).

- Naylor, Gillian (1971). The Craft Motion: a written report of its sources, ethics and influence on blueprint theory . London: Studio Vista. ISBN028979580X.

- Parry, Linda (2005). Textiles of the Arts and Crafts Move. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN0-500-28536-5.

- Penick, Monica, Christopher Long, and Harry Ransom Middle, eds. The rise of everyday blueprint: The arts and crafts movement in Britain and America (Yale Upward, 2019).

- Richardson, Margaret. Architects of the arts and crafts move (1983)

- Tankard, Judith B. Gardens of the Arts and Crafts Movement (Timber Press, 2018)

- Teehan, Virginia; Heckett, Elizabeth (2005). The Honan Chapel: A Golden Vision. Cork: Cork Academy Press. ISBN978-1-8591-8346-5.

- Thomas, Zoë. "Between Art and Commerce: Women, Business concern Buying, and the Craft Movement." Past & Nowadays 247.1 (2020): 151–196. online

- Triggs, Oscar Lovell. The arts & crafts movement (Parkstone International, 2014).

- Wildman, Stephen (1998). Edward Burne-Jones, Victorian artist-dreamer. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN9780870998584 . Retrieved 26 December 2013.

External links [edit]

- Fiona MacCarthy, "The old romantics", The Guardian, Sabbatum 5 March 2005 01.25 GMT

- Article of furniture makers of America and Canada during the Arts & Crafts Movement

- The first public museum exclusively dedicated to the American Arts & Crafts movement

- Catalog lists with images of the major American Arts & Crafts article of furniture makers Archived 2017-06-21 at the Wayback Machine

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arts_and_Crafts_movement

0 Response to "What Sub Types Are Considered Arts and Craft Style Homes"

Enregistrer un commentaire